Python logging guide - Why can't I see my logs?

What is logging and why do we need it?

My logging skills were stuck with print for quite a long while, ever since my first print("Hello World!").

I was stuck in the vicious cycle where I throw in a bunch of print statements in the debugging stage, then removing or commenting out all the print when I am nearly done, but no, there is a bug. Throw in the print statements again…

But then I came across logging, one of the elegant ways to avoid this problem. The greatest advantage of using a logging system is that you can classify log messages based on their importance, and selectively choose what level of logs to emit based on your circumstances. One can feel the necessity of a logging system by looking at the following example, which uses only print statements.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

print("Start program")

while True:

user_input = input("Enter int: ")

print(f"user input before int type cast: {user_input}")

try:

user_input = int(user_input)

except ValueError:

print(f"Given input {user_input} is not an integer. Try again...")

continue

break

print(f"user input: {user_input}")

print("Exit program")

There is nothing wrong with the code, except you cannot selectively log for the most important messages, unless you manually comment them out one by one.

Now let’s have a look at an equivalent code, now emitting messages using python’s logging module.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

import logging

logging.debug("Start program")

while True:

user_input = input("Enter int: ")

logging.debug(f"user input before int type cast: {user_input}")

try:

user_input = int(user_input)

except ValueError:

logging.warning(f"Given input {user_input} is not an integer. Try again...")

continue

break

logging.info(f"user input: {user_input}")

logging.debug("Exit program")

Now we can selectively emit log messages based on the importance that we assign. For example, after development is complete, there is little need to check for the intermediate input value, nor the start and end of the program. We usually want to look at events that are worth looking into, like when a user-given input is invalid, which may cause problems in the future.

In addition to selectively emitting logs, we may want to log the messages in a file, such as program.log, instead of the terminal (sys.stdout, sys.stderr). And in this case we may want to log messages that have a lower level of importance, compared to the one emitting to the terminal.

These problems, which cannot be solved by using print, can be solved with logging. Even better, in Python there is already the standard python logging library which implements these functionalities in a reliable and well-designed manner.

This article introduces the core objects and a little bit of internal structure of the Python logging library and two use cases (multi-module Python project, Jupyter notebook file) where one can adopt the logging workflow.

Thus, I hope everyone can learn something from this article - newcomers to logging, daily users, those already using logging but having difficulty figuring out what is going on.

The methodologies suggested in this article is one of the ways this can be done. If you know a better way, please let me know by leaving a comment!

Local Environment

- macOS Sonoma 14.2.1

- OSX arm64 (Apple Silicon)

- zshell

- This tutorial is effective as of April 2024

The logging library is a Python standard library, which means you can simply

import loggingwithout any other installation.

Logging Library Core Concepts

The Python logging library includes many objects, and unlike print we now need to determine where, how, and how much to log a message to a target log destination. This involves interacting with multiple internal objects and methods of logging, thus we need to understand the core concepts and ideas of logging objects.

This guide is not aimed to be an advanced guide, but an introduction. For the advanced guide, please refer to the advanced tutorial section in the official docs.

Logger

The most important object of the logging library is undoubtedly the logging.Logger module. It takes care of creating the LogRecord object to be passed around inside the library, and can be instantiated like this. It fetches the logger with the same name if it already exists, or creates a new one if it doesn’t.

1

2

3

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger("name of logger here")

FYI, the logging library strongly discourages instantiating a logging.Logger instance manually, like logger = Logger(). Instead, it advises on using the logging.getLogger() function.

Logger.level: The minimum level of importance a logger is willing to emit. Any messages that have a strictly lower level (same level will be logged) that theLogger.levelwill be ignored. The main levels provided by the logging library is as follows. For example, if the logger’s level is set tologging.WARNING, messages logged withlogger.debug()andlogger.info()will be ignored. A logger’s level can be set with thelogger.setLevel()method.

One thing to keep in mind, is that the level attribute is not tied to the logger only. As we will see later a handler can have a level as well.

| level | Meaning |

|---|---|

| logging.NOTSET | Level given when no level has been explicitly set. Will get into the details later. |

| logging.DEBUG | Details required in the development stage for the programmer. |

| logging.INFO | Message that the program is operating as expected. |

| logging.WARNING | Message that the program is running as expected, but may run into problems later. |

| logging.ERROR | Message that the program is not running as expected, and there is a problem. |

| logging.CRITICAL | Message that the program has ran into a severe problem. |

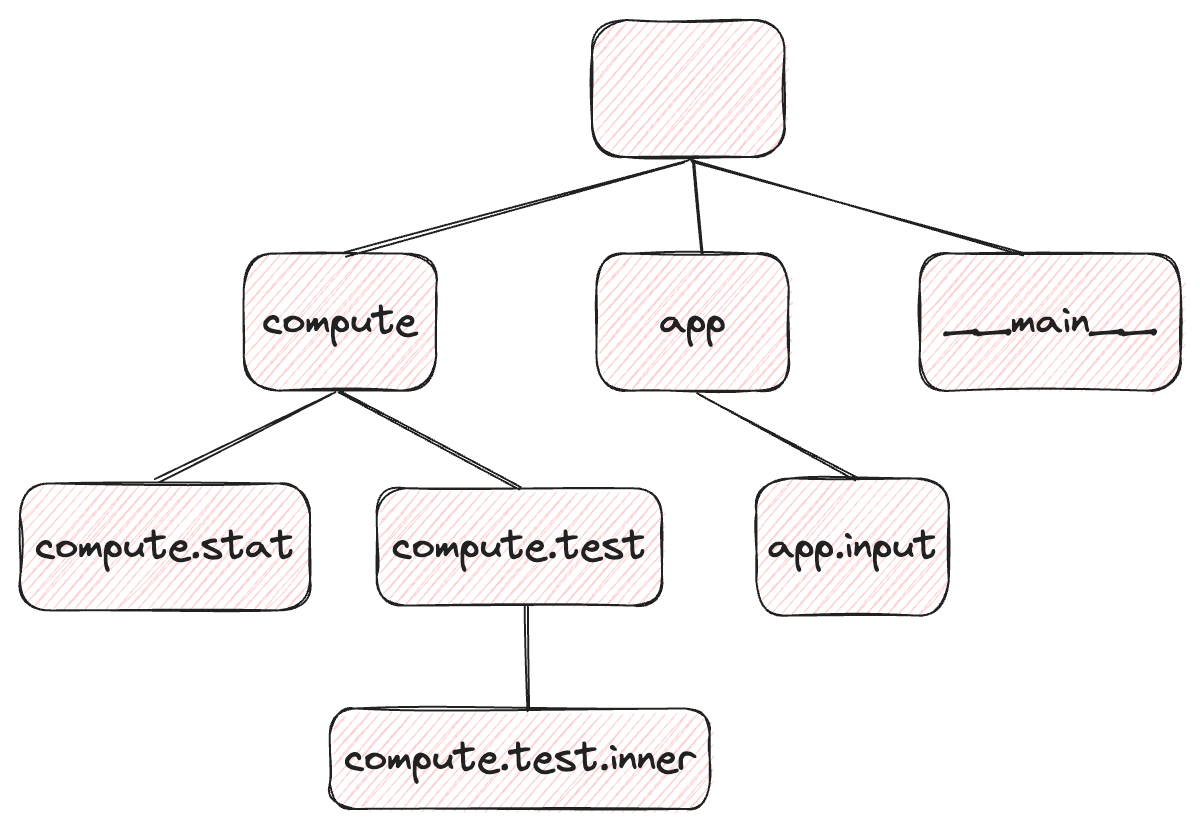

Logger.name: The name of a specific logger, set or fetched withlogging.getLogger. Apart from distinguishing the name of a logger, a logger’s name serves a crucial role functionality-wise. First of all there can be only one logger instance with the same name, and loggers have an inheritance relationship based on their name. The inheritance relationship is defined by the.string, serving as a separator for a parent-child relationship. The following diagram will elaborate.

The root logger at the top of the tree is the logger returned when no name is given, like logging.getLogger(). (If you print the name of this logger it is displayed as “root”, but as it should be the parent of all loggers if can be fetched with the empty argument) compute, app, and __main__ loggers are parents of the root logger (to make things simple, imagine an imaginary . at the front), compute.stat, compute.test are child loggers of the compute logger, and app.input is the child logger of the app logger.

This inheritance relationship between loggers is a key concept referred repeatedly.

Logger.propagate: All loggers can each have an arbitrary number oflogging.Handlers. In the above example, thecomputelogger can have n(>=0) handlers, and so does the root logger. TheLogger.propagateoption determines whether or not to propagate a log message to a logger’s parents, more specifically, to its parent’s handlers. It isTrueby default, and if that is the case a child logger’s log messages are propagated to its parent’s handlers, as well as its own handlers.

Here if a child logger and its parent logger both have their handlers and propagate is set to True, the same log message will be emitted twice, by each handler. In a typical use case we only set the handler for the root logger, and for all child loggers set logger.propagate=True, to delegate the log handling to the root logger’s handler, so this rarely happens.

logging.Handler

logging.Handler is dependent on logging.Logger, in the sense that a logger can have zero or more handlers. A handler does many things: determine whether to ignore this message, if not where and how to emit the message. StreamHandler, which emits logs to the terminal, and FileHandler, which emits logs to a file such as app.log are popular choices but there are far more than this. A user can even implement his/her own handler and incorporate it with other logging components.

Emphasized again, a handler can have a level, just like the logger.

For example, if for a single logger I wanted to log WARNING level logs to the terminal and INFO level logs to a file named app.log, I can easily implement this by having a Streamhandler with the WARNING level, and a FileHandler with the INFO level. If I add both handlers to my logger, logs will be emitted to two destinations as expected.

logging.Formatter

logging.Formatter transforms a mere string such as "start program" into a proper log message: 2024-03-26 20:11:23,203 - module1 - INFO - start program.

The formatter can be initialized like this.

1

formatter = logging.Formatter('%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

One caveat is that the formatter can only be attached to a handler, not a logger. A logger is responsible for receiving a log message and creating a LogRecord instance, and where (terminal, file) and how a LogRecord is actually emitted is the hanndler’s job. So it is more natural design-wise that the formatter should be associated with a handler, but at first it is confusing.

logging.Filter

logging.Filter literally filters the log messages based on some condition. It can be attached to a logger and a handler, but at least in my workflow I don’t use it often. It can be used to only filter the log messages with a certain name.

For instance in the above example, if "compute.test" is applied to the root logger as a filter, only log messages from compute.test와 compute.test.inner will pass, and others will be ignored.

Relationship between core components

Up to this point I have introduced the core components of the logging library. Understanding each component is importance, but what is more crucial is their relationship and dynamics.

Let’s continue on, keeping these in mind.

- Loggers maintain an inheritance relationship, according to their names.

- A logger can have 0 or more handlers.

- A logger can have 0 or more filters.

- A handler can have 0 or 1 formatter.

logging.levelcan be set for both a logger and a handler.

Why can’t I see my logs?

Now to the critical question: why can’t I see my logs?

If you have used something like logger.info() instead of print in your code, you may have ran across the problem: your logs are nowhere to be seen!

1

2

3

4

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.info("I want to log something") # this will not work :(

You finally made up your mind to introduce logging to your code. You have even called getLogger(__name__) instead of using the root logger, just as recommended in the documentation. What more do we need? What is wrong with this innocent looking code?

Journey to the center of the log

Albeit little inconvenient, now is the time to demystify logging once and for all. To achieve this we need to fully understand what happens under the hood when logger.info("message") is called, all the way up to when it is emitted.

For simplicity and brevity, I will assume there are no filters whatsoever. This means no message is ignored by a filter. Also, I will assume that the level of this log is INFO.

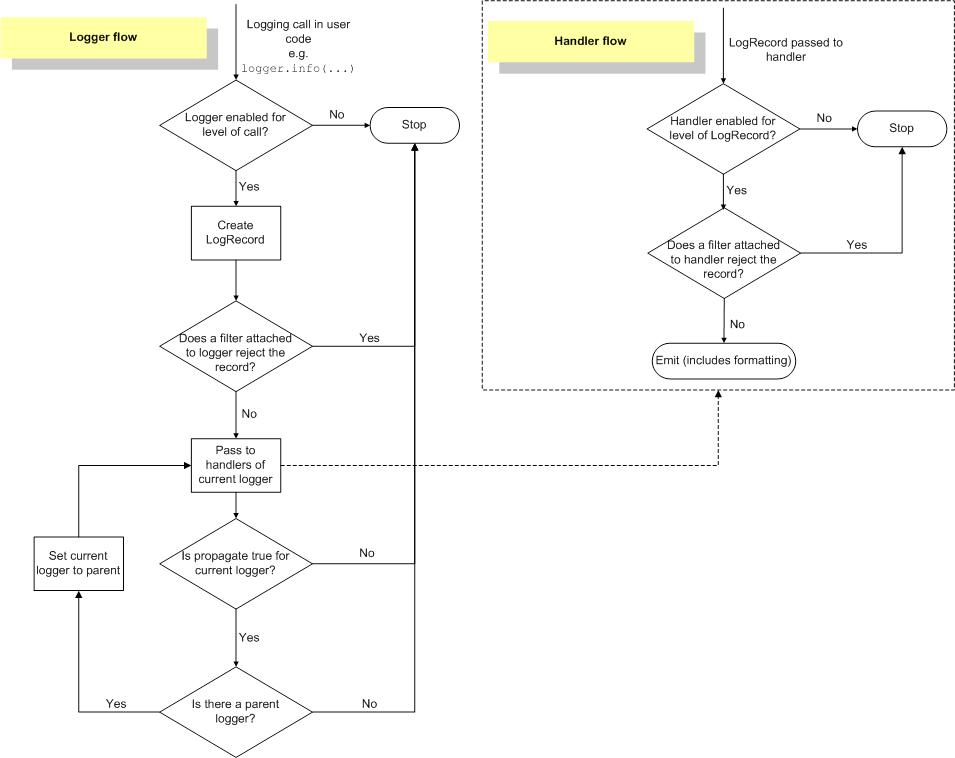

- When a message is logged with

logger.info(), first the logger decides whether or not to ignore the message. If the log level of this logger is less than or equal toINFO, the message is passed and aLogRecordinstance is made. ALogRecordis like a string, but has more information about the log message and can be conveniently passed around logging objects (this is usually referred to as a DTO, but don’t worry if you don’t know what it is). - The

LogRecordis passed to the handlers of the logger. From now the control flow moves on to the upper right side: the handler flow. - Based on the level of the handler, the

LogRecordis passed or ignored. Same as logger, if the level of this handler is less than or equal toINFO, the record passes and it is emitted to the handler’s destination. - If there are other handlers for this logger, repeat (3).

- Check whether

logger.propagate=Truefor this logger and if so, set the current logger to the parent logger, and repeat form (1). Repeat this process until we reach the root logger, the propagate is cut, or a message does not pass a logger’s level.

Now we have understood the fundamental mechanism of the logging library. Now we can investigate what was wrong with the above example, where we could not see any logs.

This is the fix.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

import logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO)

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.info("I want to log something") # this will work! :)

# Output:

# INFO:__main__:I want to log something

All we did was add one line: logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO), now everything works as intended. However, what changed because of this line is not so straight-forward.

First we need to acknowledge the following.

- The

logging.basicConfigfunction sets attributes (logger level, handlers, formatter, etc.) for the root logger. More specifically, whenlogging.basicConfig()is called A default Formatter is set to a defaultStreamHandler, and this handler is set to the root logger. - When we don’t call

logging.basicConfigor configure anything, the default level of the root logger isWARNING, and there are not handlers attached. - If you run the following script in a file named

file.pyand run it as an entrypoint script likepython file.py,__name__will be set to"__main__". Why this happens is out of the scope of this guide, so I’ll skip.

Now let’s observe the problem with the no-logger-showing code. When we create a logger with logging.getLogger(__name__), the name of this logger will be __main__. This is obviously not the root logger. This logger has no handlers attached, as we never attached anything.

Also we have not set the level for this __main__ logger. In this case the level for this logger is logging.level.NOTSET, which means that it will pass all messages and delegate to the root logger and its handler. NOTSET level is lower than DEBUG, so it will INFO will pass, at least for this logger.

Now let’s follow the journey where the INFO “I want to log something” log is correctly emitted, the code that includes the logging.basicConfig.

Two things have changed by adding logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO).

- The level for the root logger has changed from

WARNING(default) toINFO. - Previously there were no handlers for the rott logger. Now there is one handler, A default

StreamHandlerwith a defaultFormatter. As we did not set the level for this handler, the level is set toNOTSET, passing all messages for this handler.

| stage | logger name | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | __main__ | __main__ logger’s level is NOTSET. It passes, creates a new LogRecord and passes it onto the next stage. |

| 2~4 | __main__ | Skip, as this logger has no handler. |

| 5 | __main__ | propagate=True, as this is the default behavior. “main” logger passes the LogRecord to its parent logger, the root logger. In the main” logger stage nothing is emitted. |

| 1 | root | As the root logger’s level has been set to INFO, pass this LogRecord to the next stage. |

| 2~4 | root | The default StreamlHandler with the default Formatter kicks in. As the level of this handler is NOTSET, the INFO level LogRecord is emitted to sys.stderr. |

| 5 | root | As we reached the root logger and there aren’t any more handlers, return. |

We have now seen how adding a single line, logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO) has fixed the issue, and the INFO level log message is emitted as expected. The code didn’t change much, but the internal behavior did.

Advanced: when there is no handler for any loggers

You may be wondering: if we do not add any handlers to the root logger or any other logger explicitly or implicitly with logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO), can’t the root logger log anything at all?

At first, I thought that was the case. Emitting the logs is the handler’s responsibility, and without any handlers even in the root logger we should not be logging anything, theoretically. But at the same time is is rational to ignore critical logs such as logger.error or logger.critical just because the user forgot to configure the handler or misread the docs?

I thought it would be everyone’s best interest to at least log the most critical logs even with the bare minimum setup. import logging; logging.error("error occured!") logging something will be the safe option for beginners or people who didn’t care to read the documentation.

This is my speculation, but regardless of the intent the logging library has a lastResort handler, exactly for this purpose.

When no handler is attached to the root logger, a StreamHandler with a WARNING level is “attached” to the root logger as a last resort. Saying “attached” is a little weird, considering the lastResort handler is defined only in the absense of a handler, but please bear with me.

This lastResort handler is literally a last resort, so no formatting is done whatsoever and the raw message is emitted.

So in the no-log-showing example if we have used logger.warning() instead of logger.info(), the lastResort handler would have been used and we would have seen the message.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.warning("I want to log something") # this will work, but with the lastResort handler, with no formatter

# Output:

# I want to log something

But lastResort is by definition, a last resort thing, so now that we know quite deep into the logging library, let’s properly configure handlers and loggers fit to our use.

More information on this behavior can be seen in the official doc on the lastResort handler.

Logging Workflow 1: Multi-module Python project

Now is the time to actually put logging into our Python project. A typical Python project includes multiple Python files (or modules) that are packages in a nested directory structure, having distinct module names starting from the root folder. This distinct module name can be seen with the __name__ variable. For example, app.utils.calculate, backend.endpoints, app.client.database are module names.

Does this . separated structure ring any bells? Loggers have an inheritance structure based on . separated names.

Therefore, using the __name__ as a logger’s name to create a logger is a very common practice. By doing this we can delegate log handling to a parent (usually root) logger’s handlers without configuring (logger level, handler, etc.) for each module’s logger.

Also by setting a formatter at a parent level we can see where some log comes from, making the debugging process easier.

If my Python project requires one handler with one level, and don’t want to care much about configuring loggers except the entrypoint file, you can configure the root logger only like this.

In all the other files, you can simply do logger = logging.getLogger(__name__) and delegate all log handling to the root handler. Now you can simply do logger.info(), as if you were printing.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

"""Entrypoint file, entrypoint.py"""

import logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO,

format="%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s")

if __name__ == "__main__":

# do something...

# use other modules...

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

"""Any other files"""

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

# All set!

# Simply use logger.method() inside file

logger.info("log info message...")

logger.warning("log warning message...")

# ...

In this article, “file” and “module” are considered the same.

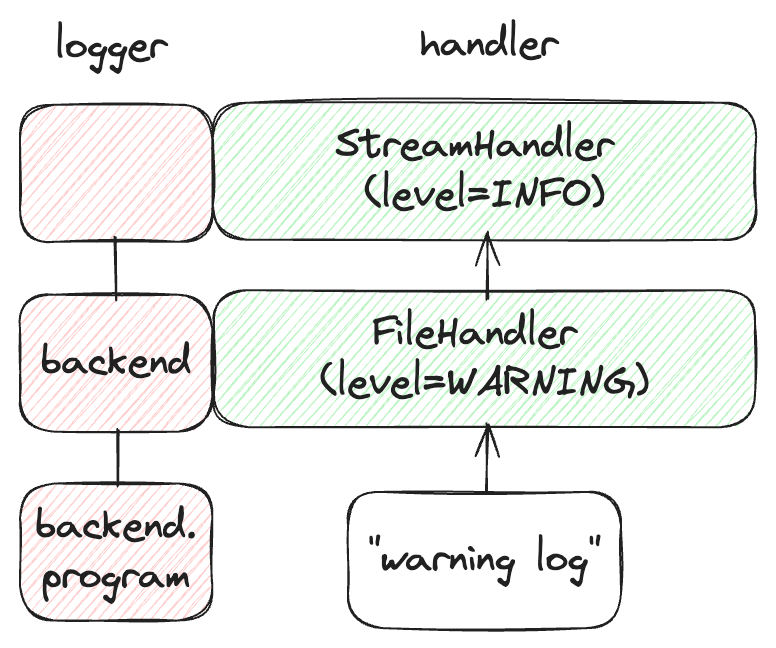

Of course now you know the inheritance relationship between loggers, you can create and set different levels and types of handlers for each module or package. For example, if you want to additionally log the logs in the backend/ directory in a file named server-warning.log for logs that are greater than or equal to the WARNING level, you can instantiate a handler inside backend/__init__.py, like this.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

"""backend/__init__.py"""

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

file_handler = logging.FileHandler('server-warning.log')

file_handler.setLevel(logging.WARNING)

formatter = logging.Formatter("%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s")

file_handler.setFormatter(formatter)

logger.addHandler(file_handler)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

"""backend/program.py"""

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

def warn():

logger.warning("warning log")

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

"""entrypoint.py"""

import logging

from backend.program import warn

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO,

format="%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s")

if __name__ == "__main__":

warn()

In the above scenario, logger.warning("warning log") will be logged both the the termianl by the root logger’s handler, and to server-warning.log by the handler in backend/__init__.py.

The inheritance relationship in this scenario can be visualized like the following.

Logging Workflow 2: Jupyter Notebook

Jupyter notebooks are usually a print madness, but inside nested for loops or inside long running functions, distinguishing DEBUG, INFO level logs can facilitate the development process a lot, as no print commenting needs to happen.

Also, as jupyter notebooks are a single-file environment, __name__ is fixed to "__main__". Therefore, we only need to worry about the inheritance relationship between the root logger and the "__main__" logger.

Personally, I don’t want care a lot about logging configuration when I am working in Jupyter notebooks, so I keep the following code block and copy-paste it in the first cell of my notebook. And that’s it! The core logging is configured for Jupyter notebook.

import logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO,

format="%(asctime)s - %(levelname)s - %(funcName)s - %(message)s")

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

One point to catch here is that as __name__ is always "__main__" in Jupyter notebooks, there is no point of including the logger name in the log. Instead, I like to include the function name (funcName) for debugging purposes. The full list of things you can include in a formatter can be seen in the LogRecord Attibute section.

Equivalent Korean Post

Python logging 가이드 - 왜 내 logging은 안 보일까?

References

- https://docs.python.org/3.11/library/logging.html

- https://docs.python.org/3.11/howto/logging-cookbook.html#using-logging-in-multiple-modules

- https://docs.python.org/3.11/howto/logging.html#what-happens-if-no-configuration-is-provided

Please feel free to point out any inaccurate or insufficient information. Also, please feel free to leave any questions or suggestions in the comments. 🙇♂️