Git Rebase & Fast-forward Workflow Tutorial

Who should read this?

Those familiar to using git alone, but not so much in a collaborative setting.

What is a git branching strategy and why do we need it?

In collaborative software development settings, many people work on different features in a single code repository. This inevitably leads to nasty conflicts, messy commit history, and confusing version control. Thus, it is important that all members of the team agree on one branching strategy to merge different feature branches.

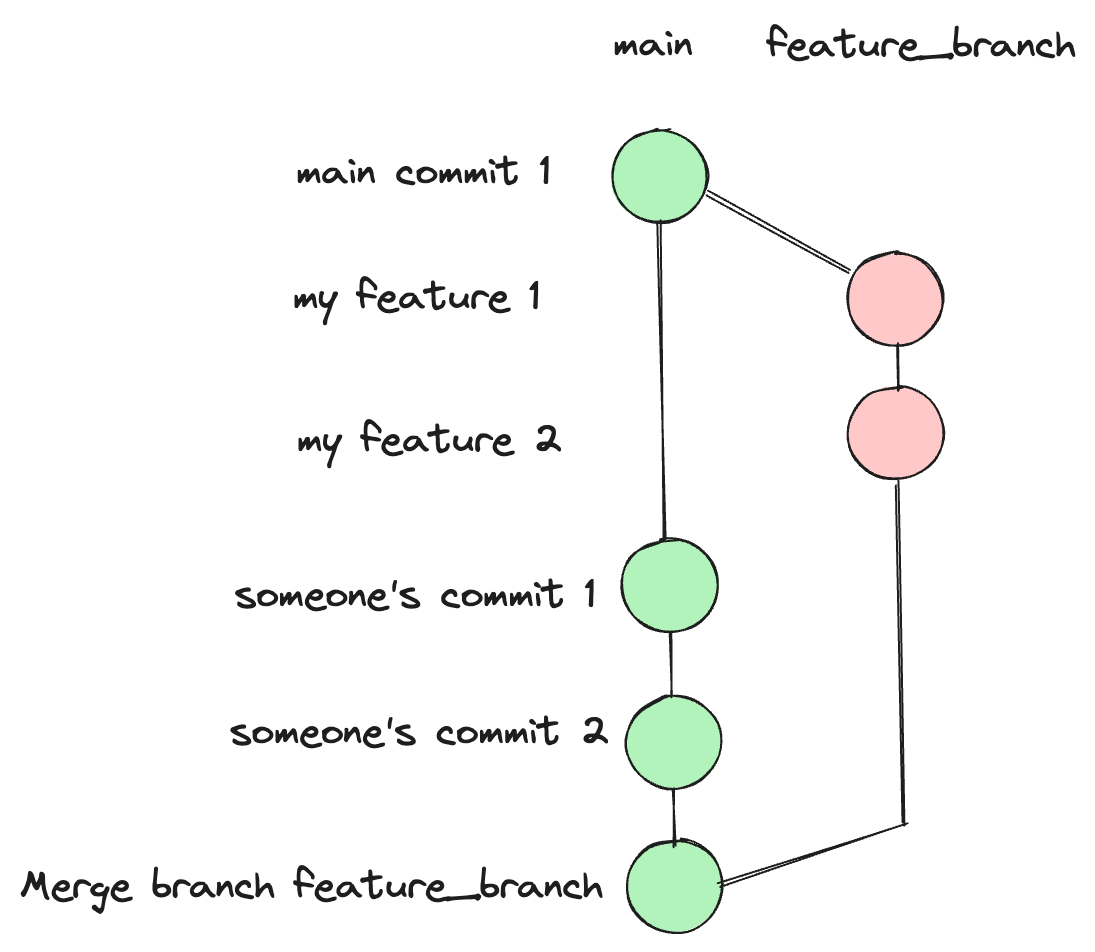

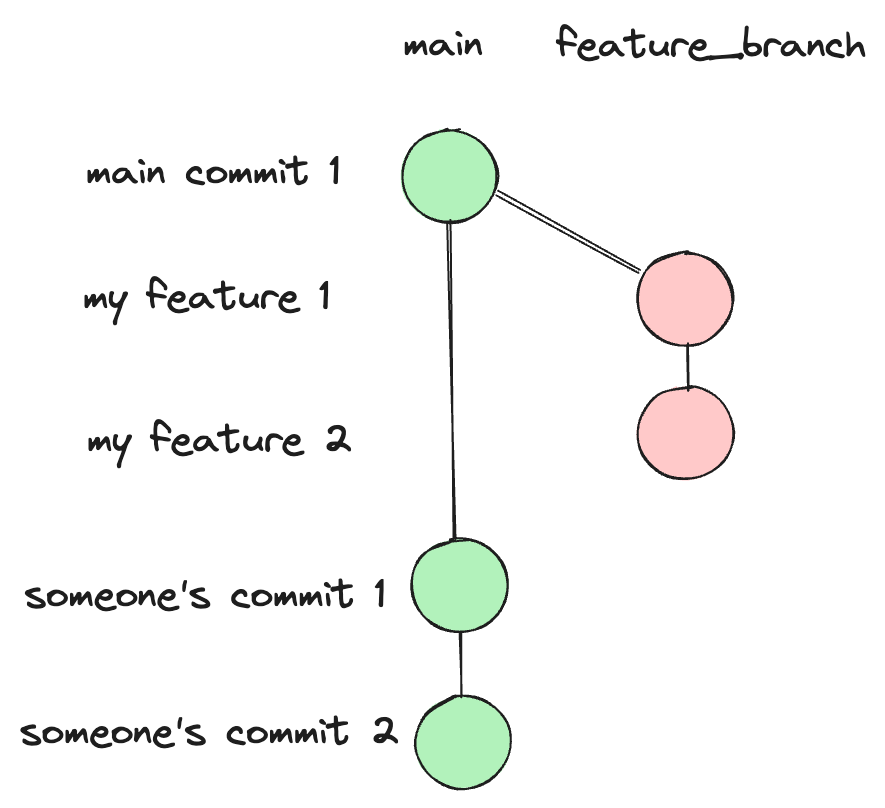

A git “branching strategy” is a method to combine two diverged branches into one. For example, here is a most common situation where a branching strategy is required. There is a feature_branch, which has been branched off of main. The feature_branch pushed its own commits and has diverged from where it has left off. What makes the situation complicated, is that the main branch may have also moved on from where feature_branch has left off. This situation can be illustrated like this.

How do we combine these two diverged branches? There are mainly two methods: the “merge” strategy and “rebase and fast-forward” strategy. Teams adopt either one depending on their policies and preferences.

In this post, I will compare the two code combining methods, illustrate the typical “rebase and fast-forward” strategy, and discuss its advantages and disadvantages.

The example discussed in this post can be found in my repository.

How are the strategies different?

For simplicity, assume that in the below example an automatic merge/rebase is available, meaning there is no conflict when combining main and feature_branch. Handling git conflicts is not the scope of this post.

Merge Strategy:

This strategy creates a new commit named Merge branch feature_branch, which applies both changes from the two branches and merges them into one.

Note even after the merge, we can still see that the feature_branch is still diverged from the main branch. At the end of the day, from main branch’s perspective, when a branch is merged, only a single merge commit containing all changes from feature_branch is newly committed.

Rebase & Fast-forward Strategy

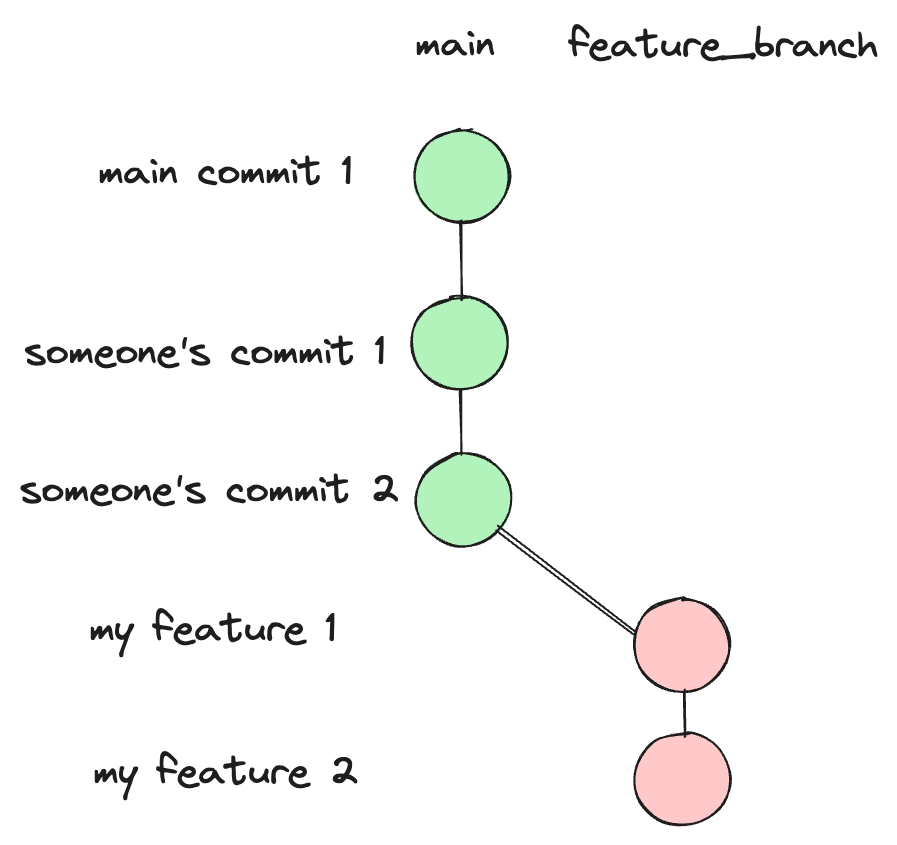

On the other hand, the rebase & fast-forward strategy first applies all the commits of feature_branch on top of latest main, like below. In git lingo this is referred to as “rebasing”, as it is moving the “base” of the feature_branch from main commit 1 to someone's commit 2 (the tip of latest main branch), hence the term “rebase” makes much more sense.

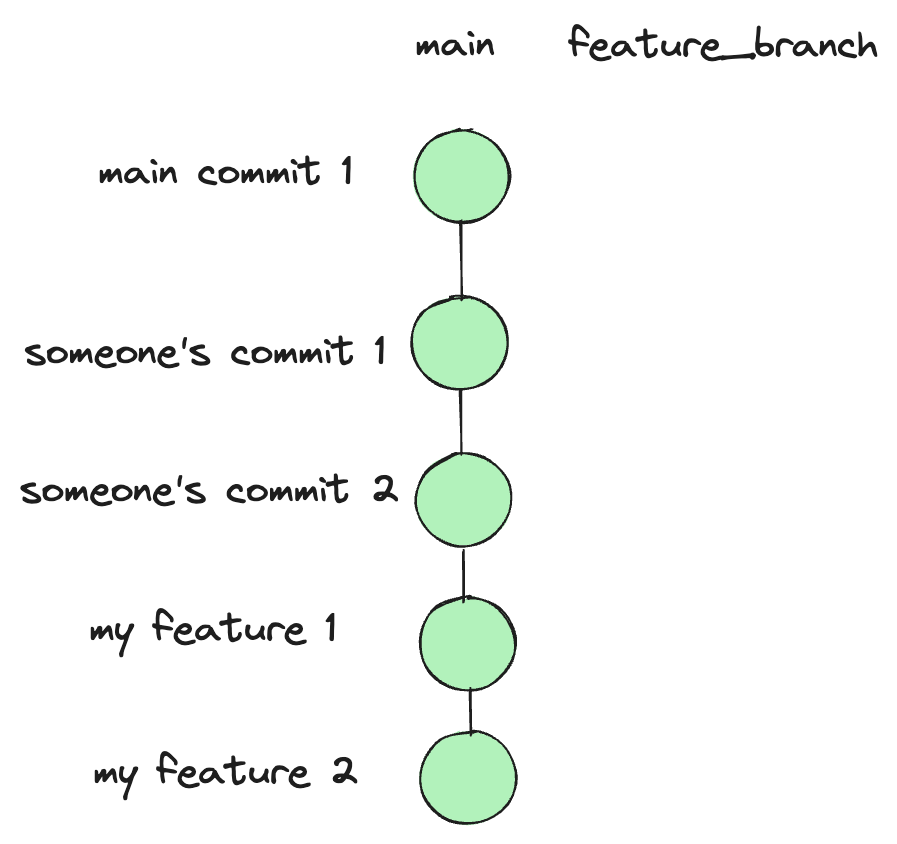

Then, it “straightens up” the commit history like this. In git lingo this is referred to as “fast-forwarding”. This is related to how git keeps track of commit history and how it switches from one to another. When checking out a specific version or commit in its history, git simply makes its “HEAD” point to that commit, similar to making a C/C++ pointer point to a different value. Previously, the latest main branch points to someone's commit 2, but as the commits on the feature_branch is rebased, now all git needs to do to incorporate these changes is to move the HEAD to my feature 2.

Personally, I prefer this strategy over the merge strategy as it leaves a clean and linear history, although each team would have their own preferences based on their use cases. However, one use case I find the rebase and fast-forward especially useful is when performing a git bisect operation. The git bisect operation is useful when you need to find which commit introduced a bug in your overall codebase, based on a binary search. As with the merge strategy all changes from the feature branches are stuffed inside a single merge commit in the main branch, the power of git bisect cannot be fully empowered.

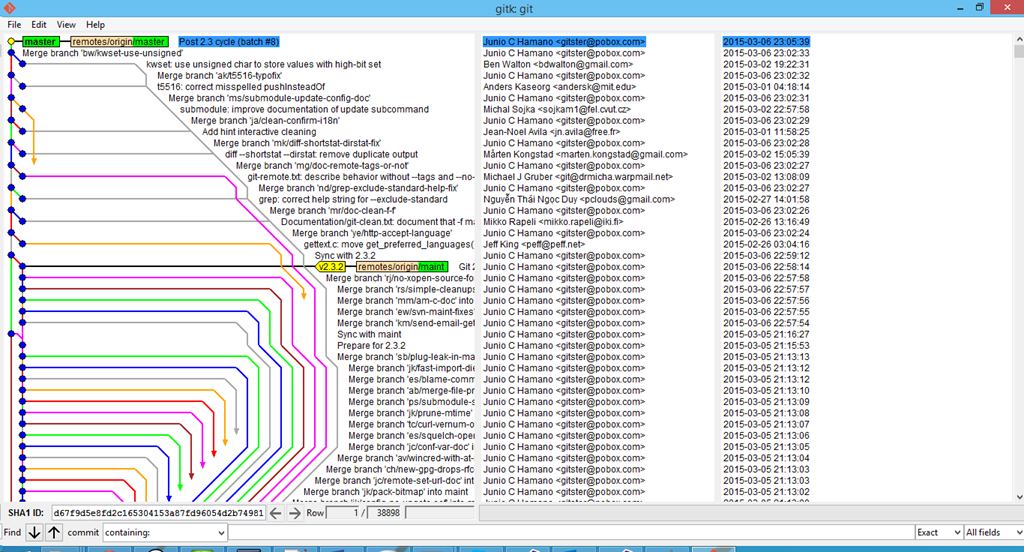

Also, in the merge strategy if there are branches that are branched off of branches other than main and there are merge commits that merge main to keep track of latest changes, the branch history can be almost cryptic. Here is an example of “merge hell”. 🥲

Of course, here I am cherry-picking the good features of my preferred approach. When incorporated responsibly by all members, the merge strategy can also work fine. Still this post deals with my preferred option, rebase & fast-forward strategy, and its typical workflow. I will address the disadvantages and caveats of the rebase approach in later sections.

Local environment

- macOS Sonoma 14.2.1

- OSX arm64 (Apple Silicon)

- zshell

- git version 2.38.1

- This tutorial is effective as of July 2024

Prerequisites

This tutorial assumes the audience to be familiar with the following concepts/tools.

- Basic git for personal usage (git knowledge except collaborative usage such as git pull, creating pull requests, git merge, git rebase, etc.)

Rebase and Fast-forward Workflow

1. Sync up with the most recent version of main branch

To minimize the chances of creating a conflict, diverge off the most recent version of the main branch.

1

2

git checkout main

git pull

2. Make a feature branch

1

git checkout -b feature_branch

3. Write good code!

1

# Lots of good code

4. Add and commit your changes locally

1

2

git add .

git commit -m "Useful commit message"

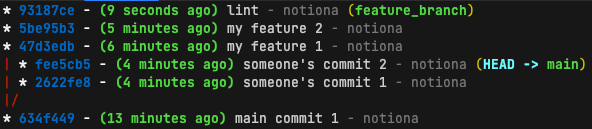

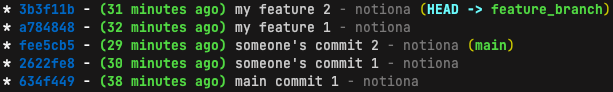

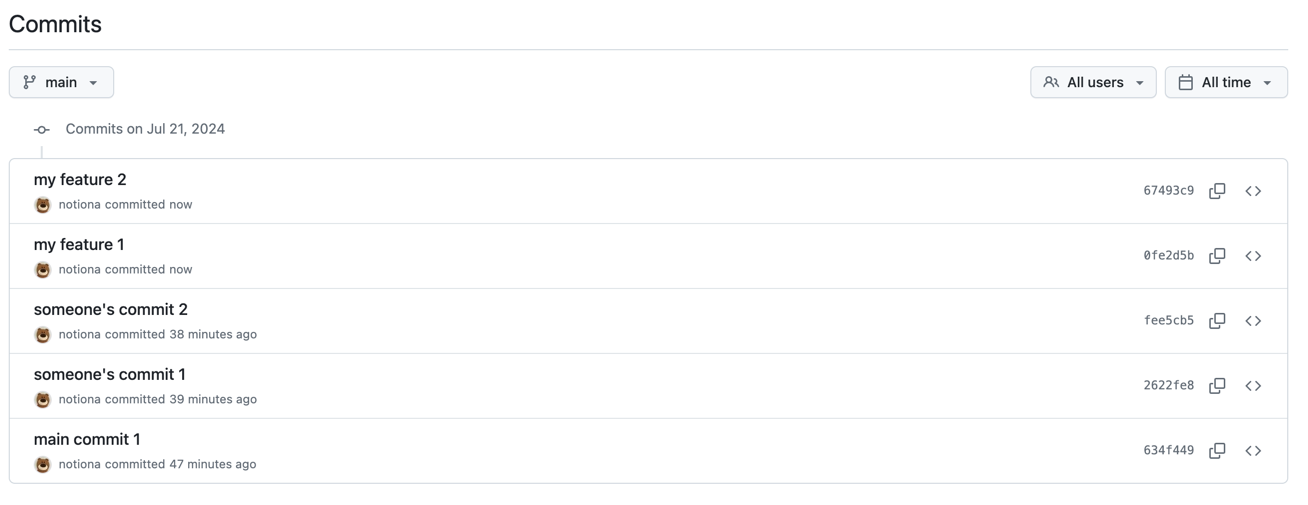

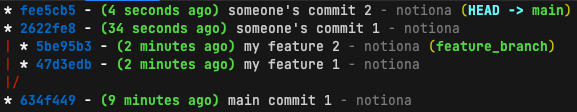

Up to this point, I have set up the git commit history to look just like the example we have seen earlier. The only difference is that in the command-line git log diagram the most recent commits are at the top.

5. Squash your commits into logical components

In most cases, your local commits in your feature branch are not in logical components, but in more chunks, possibly due to linting or minor fixes along the way. Let’s say you made a minor lint change, that you would rather have “squashed” into your latest commits.

In this case “lint” commit would rather be squashed into the previous commit, “my feature 2”.

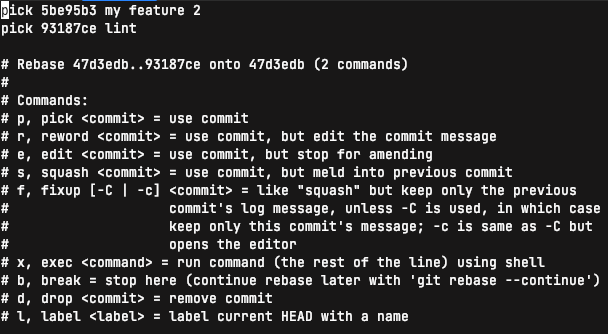

In order to “squash” minor commits to make them into logical components, use the below command.

1

git rebase -i HEAD~n # n is the number of recent commits to fix

This will open a text editor window with the most recent n commits. For the commits you would like to squash into the previous commits, change the ‘p’ (pick) into a ‘f’(fixup).

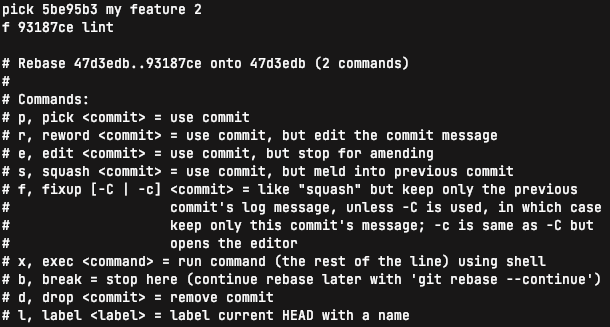

If you save and quit, the commits that you marked as ‘f’ will be squashed into previous ones, as if they never existed on their own!

After saving, the last commit is “squashed” into the previous commit, as desired. One point to note is that, the commit hash of “my feature 2” has changed - since it is now a completely different commit. This is an important feature of git rebase - git rebase can rewrite history, making it a destructive operation.

6. Pull the most recent version of main branch

Even as we were working, main may have new commits. So just in case, do a fresh pull to check.

1

git pull

7. Rebase with the main branch

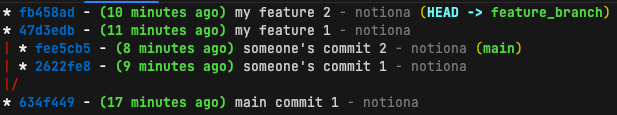

This command applies all the changes that were made in main into the feature branch after its diversion. The two diagrams illustrate the effect of this command.

1

git rebase main

Now the commits are straightened, and my local changes come after the most recent commits of main.

8. Push these changes to remote

Push the rebased feature branch into remote.

1

git push -u origin feature_branch

If you have already pushed your feature branch to remote and you do a rebase on a newer main, as discussed above, your commits will all have completely new git hash ids. This means you need to inevitably forch push (

git push -f) to sync your newly rebased changes to remote, instead of simple git push.

Since your feature branch is yours and yours only (hopefully), force pushing is acceptable. If multiple people are working on your feature branch, you should be very very CAUTIOUS and DO NOT FORCE PUSH right away, unless you have discussed with your coworkers working in the same branch and know exactly what you are doing.

9. Make a PR in GitHub

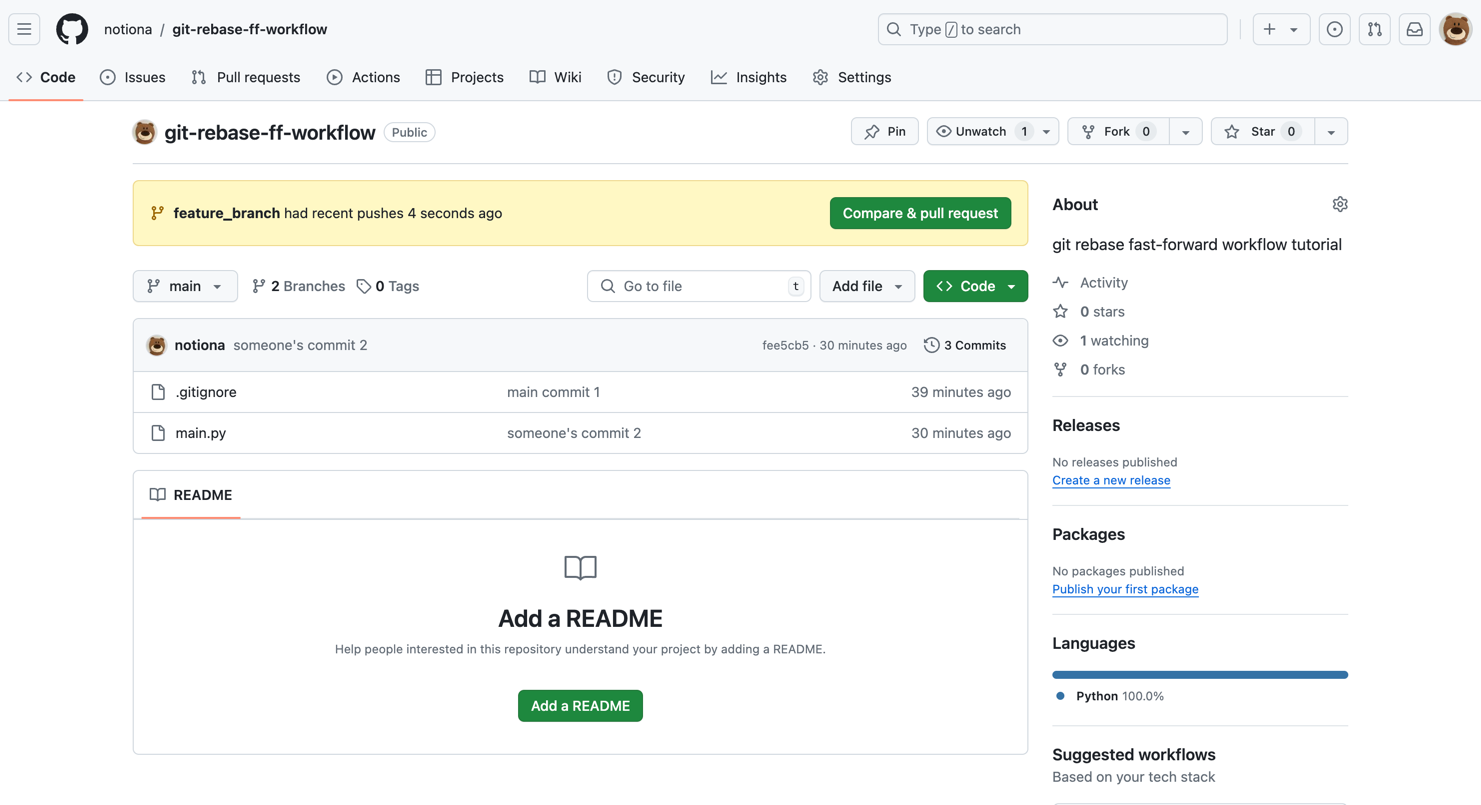

Click on “Compare & pull request”.

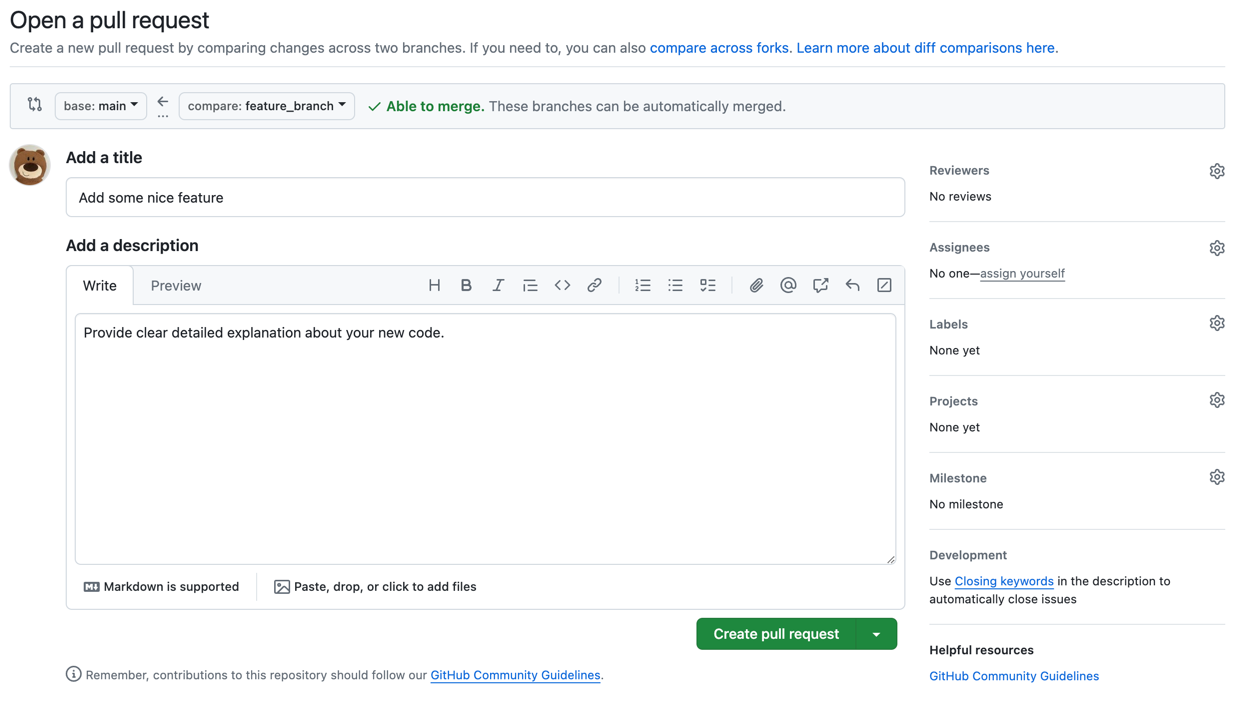

According to your work, write a sensible pull request, assign reviewers, labels, projects, etc. Then create the pull request.

10. Merge this PR into main

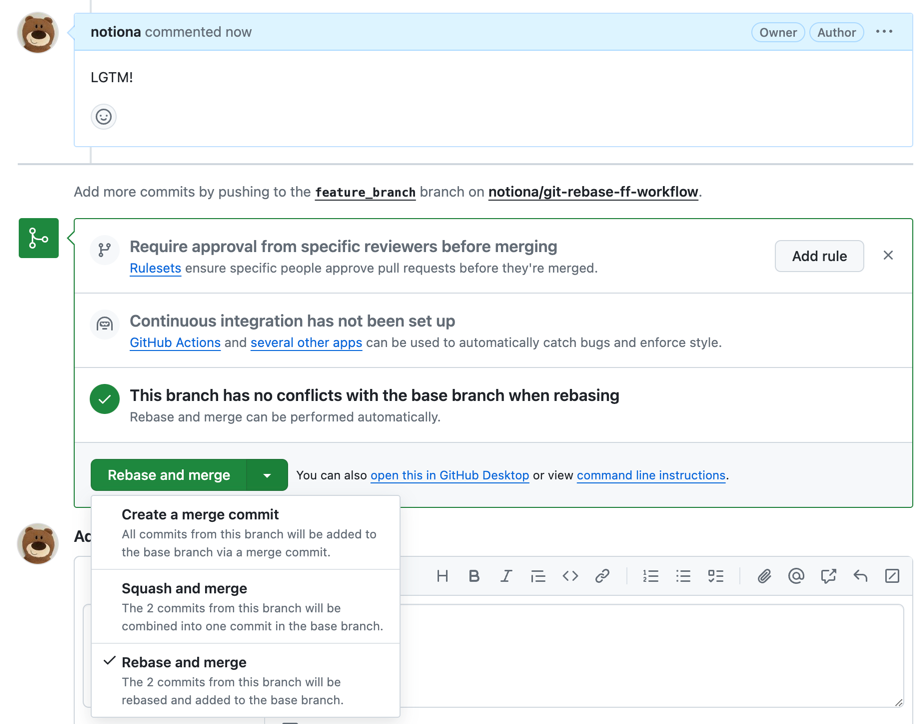

When reviewers have approved your pull request, all the checks have passed, and there is no merge conflict, select “Rebase and merge” option and confirm the merge.

“Create a merge commit” is the merge strategy we have discussed above. The other unfamiliar option, “Squash and merge” is just like “Rebase and merge”, except all the commits in your pull request will be squashed into one single commit before getting merged into

main.

Now that the change has been successfully merged, you can choose to delete the feature branch.

Now in remote a beautiful, linear history has been made.

The example discussed in this post can be found in my repository.

Downsides / caveats of the rebase fast-forward strategy

Now that I have illustrated the full workflow, now is the time to discuss the disadvantages and caveats of the rebase and fast-forward strategy, based on my experience. These are the cost you would need to pay to maintain a linear git history with rebase and fast-forward.

Conflicts when catching up with latest main

While working on your feature branch, there may very well be new commits in the remote latest main. To catch up, you must frequently git rebase origin/main. If there is any conflict, you must resolve them. Although resolving git conflicts is not in scope of this post, resolving conflicts for rebase is much more painful than in the merge strategy. For the rebase strategy you need to resolve conflicts for each new feature commit in your branch, instead of one for the merge strategy. In the worst case scenario, you may need to resolve git conflicts for every commit in your feature branch.

Potentially destructive outcome when multiple people are working on the same feature branch

As seen above, when rebasing all the commits in the rebased branch are “newly written”, implying that git rebase is a destructive operation. Usually a single feature branched is used by a single person, but when multiple people are working on a same feature branch, the rebase and fast-forward strategy needs extra attention and communication. This is because when multiple people are working on the same feature branch, there is a possibility you may overwrite or destroy someone else’s work that is pushed to remote. git push -f is always dangerous and needs a lot of care and attention. Once again, with great power comes great responsibility.

Equivalent Korean Post

References

Please feel free to point out any inaccurate or insufficient information. Also, please feel free to leave any questions or suggestions in the comments. 🙇♂️